ONWARD!

Thank you for the 70th Flaherty Film Seminar

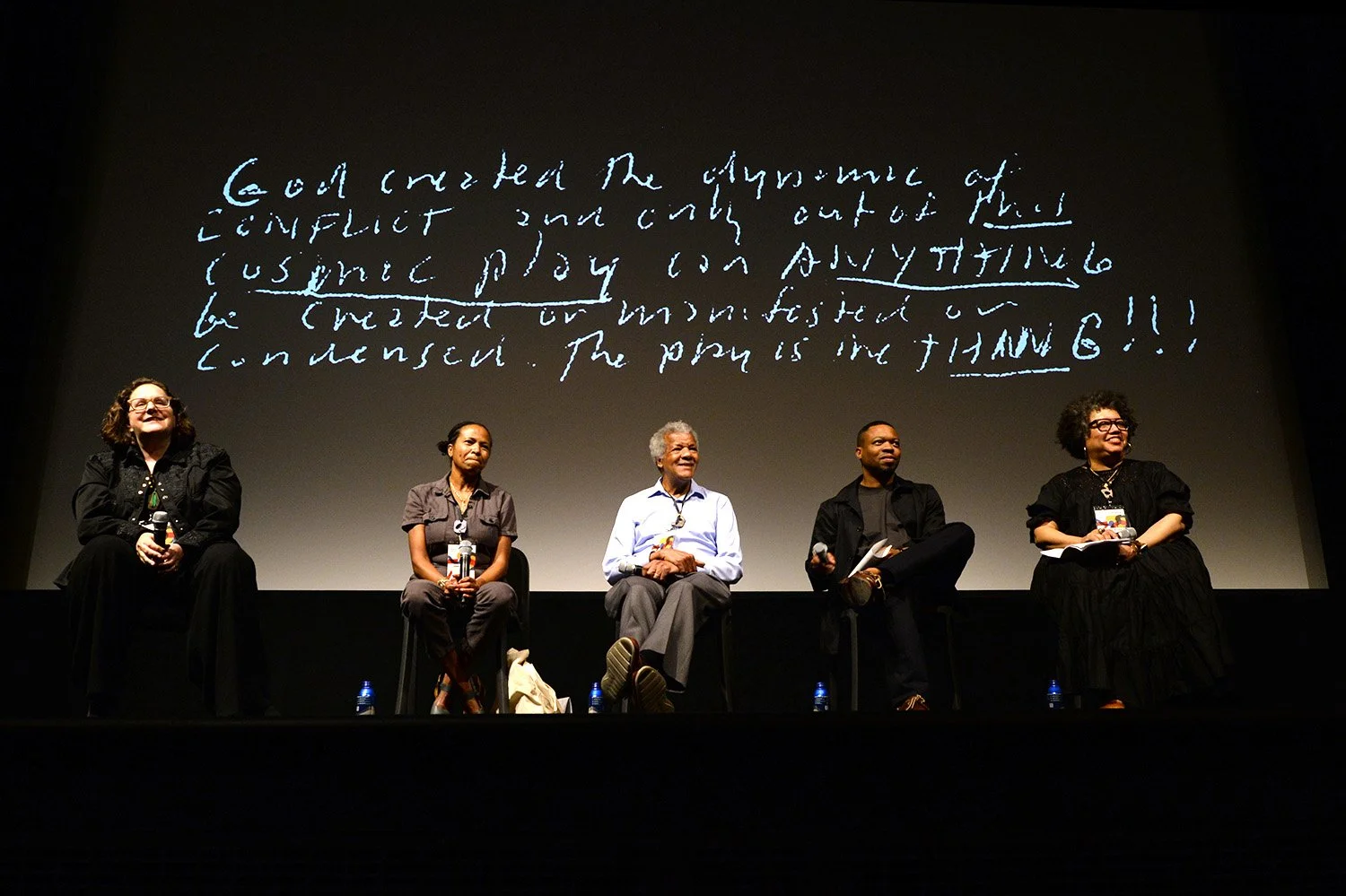

Thank you to the over 1400 people who joined us for the 70th Flaherty Film Seminar, Onward!

This includes over 400 people in New York City, 350 Pod Participants, 150 Online Participants, and over 500 people forming Gatherings around the world.

The Onward! seminar took place in over 45 Countries and fostered hundreds of conversations in dozens of languages, alongside a multitude of questions — such as the following, drawn from virtual.theflaherty.org:

How can cinema help us go ONWARD when the whole world, or what looks like the whole world, is so determined to drag us backward, downward, hellward? - from Salaya, Thailand

How can cinema not be separate from the world, but emanate from it, exist within it, become a nutrient in its very soil - how can the world then begin to emanate from its cinema? - from New Delhi, India

Is it possible to create a network that allows us to continue sharing voices and perspectives in these turbulent times? - from Bogotá, Colombia

How can we continue to build from our practices and collectives more spaces of resistance, struggle, dialogue and hope? - from Limá, Peru

Can we build new vocabularies for images and resistance? - from Porto, Portugal

For you to explore: our Archive of ONWARD!

Our website is now updated with the following information about the Onward Seminar experience. Whether you were able to join the seminar in June / July or are curious to know more, we invite you to spent time with our archives:

PROGRAM | FILMS | ARTISTS | FELLOWS

ONLINE EXPERIENCE | PODS | GATHERINGS

TEAM | PARTNERS

PHOTOS

THANK YOU to our 2025 Seminar Artists!

We are grateful to all the artists were present in various forms of the Seminar this year. Thank you to following artists whose works were shared on our cinema screens!

Activist Archivists*

Akram Zaatari*

Alejandro de los Rios, NOVAC*

Alex Rivera*

Anahita Razmi

Angela Park, Norbert Shieh, Visual Communications*

Asim Aziz*

Bill Brand

Camille Billops

Carlton Jones, Louis Massiah, Scribe Video Center*

Cauleen Smith

Charles Raboteau, Gail Loney, Jacqueline Wiggins, Marcus Rivera, Tinamarie Russell, William Michael, Scribe*

Haskell Wexler

Ignacio Agüero

James Blue with Adele Naude Santos*

Jazmin García*

Jeanne Keller, New Orleans Video Access*

Jocelyne Saab*

Jon Goff, George Twopointoh, Compton A. Timberwolf

Karrabing Collective

Larissa Sansour*

Louis Massiah, Terry Rockefeller

Madison Buchanan, Appalshop*

Maria Estela Paiso*

Maxime Jean-Baptiste

Meriem Bennani*

Myriam Charles

Omar Amiralay

Orlando Ford, Detroit Narrative Agency*

Otolith Group

Sara Gomez

Sofía Gallisá Muriente*

Sudanese Film Group

Tim, Rio, B Media Collective*

Tony Buba*

Victor Jara Collective*

William Greaves, David Greaves, Liani Greaves

*Fellows Only Programs

The 70th Seminar took a village: thank you to all who contributed

Seminar Programmers

Carlos Gutiérrez and Zaina Bseiso

Richard Herskowitz and Louis Massiah

Janaína Oliveira and Christopher Harris

Fellowship Program Contributors

Jemma Desai and Ethan Philbrick

Fellowship Doulas

Lynne Sachs, John Muse, Samia Labidi

Pod Managers

Aisha Jamal — Toronto

Chalida Uabumrungjit, Kong Rithdee & Sanchai Chotirosseranee — Thai Film Archive

Mariale Mosquera — Cinemateca de Bogotá

Emile Fegté / Klein — Los Angeles

Maile Costa Colbert — Lisbon

Anuj Malhotra — New Delhi

Amarante Abramovici — Porto

Magdalena Kielbiowska — Warsaw

Thank you too to our numerous facilitators, in NYC, and in Pods & Gatherings.

Our Team

The Flaherty in its 70th year is composed of:

Samara Chadwick – Executive Director

Juan Pedro Agurcia – Program Director

Anne de Mare – Grants and Special Projects Lead

Anisa Hosseinnezhad – Fellowship Programmer

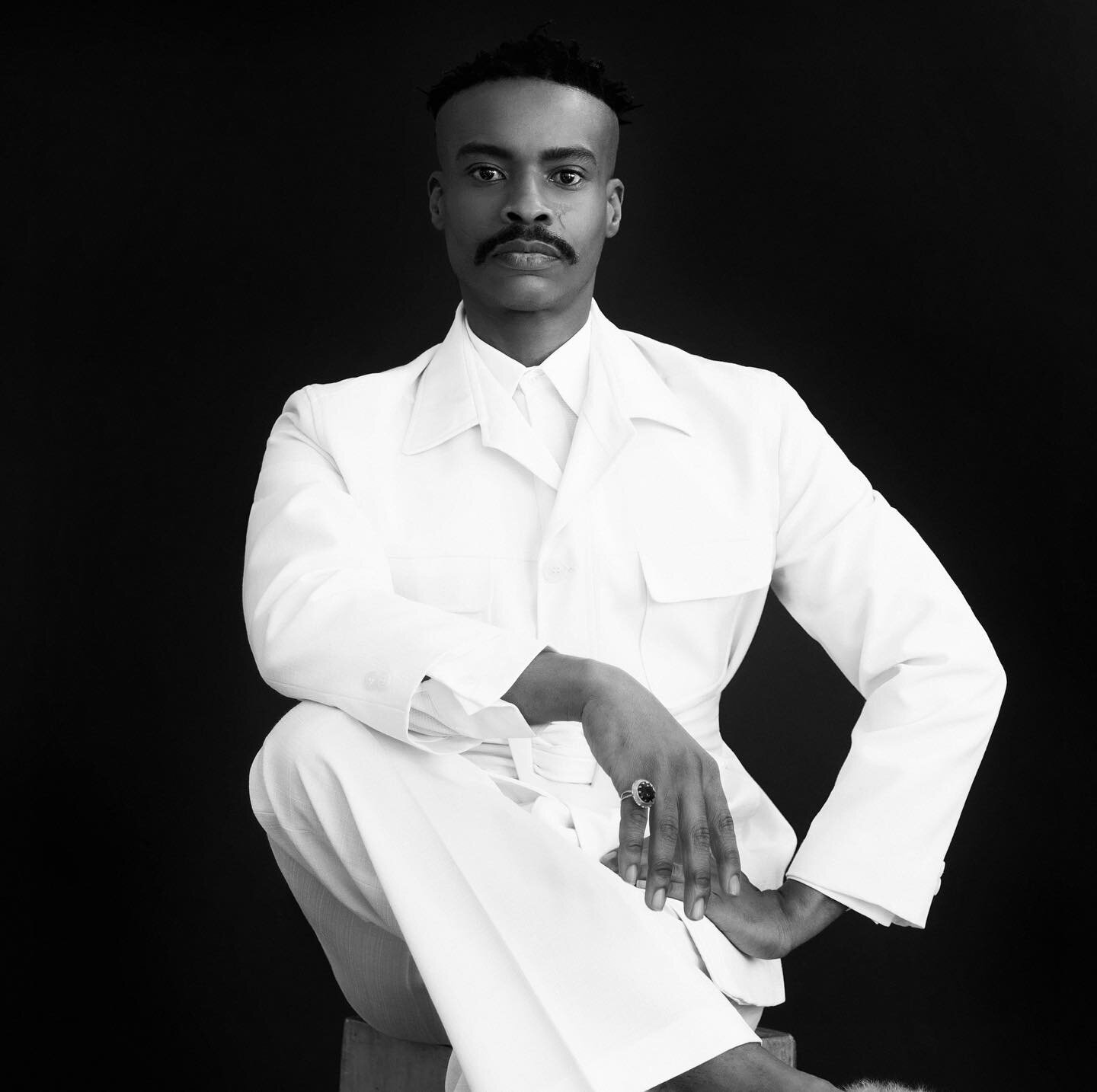

Maliyamungu Muhande – Brand Art Direction

Zile Liepins – Graphic Design & Photography

Simone Barros – Programs Coordinator

Elizabeth Kroner – Production Coordinator

Nehal Vyas – Online & Digital Communications Coordinator

Michael Krish – Online Advisor

Eynar Pineda – Production Consultant

Jules Rosskam – Online Fellowship Coordinator

Sun Park – Fellows Coordinator

The Flaherty Board of Directors

Pablo de Ocampo, President

Dessane Lopez Cassell, Vice President

Ted Kennedy, Treasurer

Patti Bruck

Steve Holmgren

Ruth Somalo

Juana Suárez

The Flaherty thanks all our partners, who support the Seminar, Fellowship, Pods,

and our wider work as an independent organization.